Introduction to cryptography (CSCI 2824, Spring 2015)

In this note, we study a few key topics in cryptography:

private key encryption

public key encryption

authentication

Cryptography

What is cryptography? And why is it important?

Crypto: Secret and graphy: writing.

So cryptography is the study of techniques for encrypting and decrypting secrets. With the advent of internet and the need to keep communications across networks secret, cryptography has emerged as an important discipline of computer science and a great application of advanced mathematical techniques to the field.

Example 1: Secrecy/Privacy

Imagine Alice and Bob wish to share a secret message between themselves. However, they cannot meet in person in a safe place to do so. Let us suppose the secret message is Party 6:00 p.m, Friday at Zolo's. – Alice.

Let us suppose the secret society (or the government) is quite interested in crashing AliceBob's party. Therefore, it is important for AliceBob to code up their message so that the secret society does not get wind of their party.

Example 2: Authentication

In this scenario, let us say that Mr. Ty Coon would like to buy

an oil rig in the middle of campus for  .

So he sends a message to the president of the university:

.

So he sends a message to the president of the university:

Dear President,

I intend to purchase mining rights to the oil reserves underneath your campus for $100000.56 . Students and faculty can be hired to work in this rig for a generous salary of minimum wage.

I remains yours truly,

Mr. Ty Coon

How is the president to know that this important message is from Ty Coon himself as opposed to some student playing a prank? In other words, is there a way that Ty Coon can sign the message so that everyone can authenticate the message as a genuine message from him?

Web

As commerce over www is widespread, people send money over the internet in the form of credit card numbers and payment instructions to banks. Agreements are digitally signed over the network and people log in to secret networks over VPN. All of these nice things are powered by cryptography.

There are two basic types of cryptography:

Private key cryptography;

Public key cryptography.

Private Key cryptosystems

Private key cryptography consists of encrypting a message  using a secret password

using a secret password  (a.k.a the private key).

Anyone possessing the password can then decrypt the message.

(a.k.a the private key).

Anyone possessing the password can then decrypt the message.

Let us take look at some simple private key algorithms, using (1) shift ciphers, and (2) XOR.

Warning: The schemes below can be broken very easily. So do not attempt this.

Shift ciphers

One of the oldest cryptosystems uses the shift ciphers,

which make use of simple modular arithmetic.

Suppose we assign a number to each of the 26 English alphabets

(e.g.  ,

,  , …

, …  ).

).

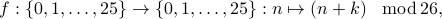

A simple way to encrypt a message is to use the shift cipher, i.e., a function of the form

where the encryption key  is an integer.

is an integer.

For example, the message HELP could be encrypted as KHOS. Here the encryption key is 3.

It is very easy to crack a shift cipher and guess the encryption key. One slightly more sophisticated cipher is to incorporate a prime multiple:

where  is an integer and

is an integer and  is a prime number.

is a prime number.

XOR

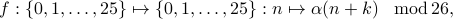

Let us encode the message into  bit chunks

(e.g., ascii characters).

bit chunks

(e.g., ascii characters).

Example: Show me da money. The ascii codes are S = 83, h = 104,….

Therefore, the message can be represented as:  .

.

For simplicity, we can choose the password as a 8 bit string. Example:

Each  bit ascii character

bit ascii character  is encrypted as:

is encrypted as:

where  denotes bitwise XOR.

denotes bitwise XOR.

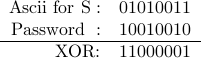

Example: Using password  above, the character

above, the character  can be encoded as

can be encoded as

Similarly, other letters can be encoded in the same way.

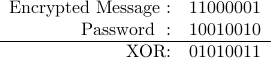

To decode, we then XOR the encoded message with the same password  .

.

Example (decryption):

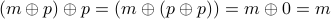

The main property of XOR that is being used here is  for all

for all  . Therefore

for message

. Therefore

for message  and password

and password  ,

,

Since it translates every character to a different one

(for example, 'S’ (ascii 83) -> ascii 161),

it is in effect a transposition cipher.

Since it translates every character to a different one

(for example, 'S’ (ascii 83) -> ascii 161),

it is in effect a transposition cipher.

Drawbacks of the above cryptosystems.

Both of the cryptosystems are very easy to crack.

They can be broken by analyzing the relative frequency of coded letters and comparing with frequency in the english language. E is the most commonly used letter, followed by A,O,I, and so on.

Another type of attack is called known plaintext attack. Let us say, in the case of XOR-crytosystem, we know the original message

and the encrypted version

and the encrypted version  somehow,

we can guess the password simply as

somehow,

we can guess the password simply as  .

.

DES

DES stands for Data Encryption Standard. It was proposed by IBM researchers in the early 70s with the help of NSA. At a high level, you can think of DES replacing the XOR bitwise operator for a much more complicated looking function. In fact, the function is specified at its core using lookup tables called S-Boxes. DES uses many tricks to guarantee good security. Yet, it is not unbreakable. For instance, DES uses a 56 bit password (recently upgraded to 64 bits). It can be broken if someone is willing to invest very large amount of computation to brute force the password or use a more intelligent scheme.

Public Key Cryptography

Public key cryptography is very interesting idea that was first invented by British intelligence in the late 60s but kept a secret. It was rediscovered and publicized by Rivest, Shamir and Adleman (RSA) in 1975. Since then it has been a key achievement of number theory in computer science.

Basic idea behind public key cryptography

One can imagine a cryptosystem as a lock that protects a secret. Private key cryptography can be thought of as a traditional lock and key system. The key is the password and if one has the key or can forge one, then one can break into the contents of the box by opening the lock.

Public key cryptosystems are much more interesting. Imagine a lock with two types of keys: a private key that only one person has access to (ideally) and a public key that anyone can obtain. Imagine the lock as operating in one of two ways:

If locked with a private key, it can be opened with a public key by anyone. (This scenario arises when authenticating a message.)

If locked with a public key, it can be opened by a person with a private key. (This scenario arises when encrypting private messages.)

How can such a scheme help?

Example 3: Secrecy/Privacy

Recall the secret message Alice wishes to send Bob: Party 6:00 p.m, Friday at Zolo's. – Alice. Imagine that every person has a private and a public key to their own box. Then Alice can send the secret message to Bob using the following procedure.

Alice takes Bob's public key.

Alice codes up the message using Bob's public key, and send it to Bob.

Since Bob alone has the private key to his box, the message cannot be opened by anyone else.

Example 4: Authentication

Suppose Ty Coon writes the letter: Dear President, I intend to purchase mining rights to the oil rig in your campus for $100000.56 . I remains yours truly, Mr. Ty Coon

Is there a way that Ty Coon can sign the message so that everyone can authenticate the message as a genuine message from him? Let us say that TyCoon has a private and a public key. How can TyCoon convince the president of his message's authenticity? Hint Use public/private keys.

RSA

Can we really simulate private/public keys in practice? Yes. This is where number theory comes to the rescue in the form of the RSA cryptosystem.

Here is the basic idea:

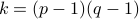

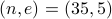

Take two large prime numbers

. These have to be large: let us say

. These have to be large: let us say  digits.

digits. Compute their product:

. Also compute

. Also compute  . After that destroy

. After that destroy  .

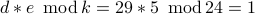

.We compute a number

that satisfies:

that satisfies:  such that

such that  is not a factor of

is not a factor of  .

.Find numbers

so that

so that  . A fundamental result in number theory (the Euclidean algorithm)

says that we can always do so.

. A fundamental result in number theory (the Euclidean algorithm)

says that we can always do so.Finally, we keep

and discard

and discard  .

.  forms the public key and

forms the public key and  the private key.

the private key.

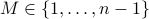

We can send an encrypted message  to Alice using the following

procedure, if Alice has the public key

to Alice using the following

procedure, if Alice has the public key  and

the private key

and

the private key  constructed as described above.

constructed as described above.

We take her public key

.

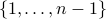

.Represent

represented as numbers from

represented as numbers from  .

(If the message is large, break it down into blocks

that can be represented by

.

(If the message is large, break it down into blocks

that can be represented by  .)

.) The encrypted value of

is

is  .

.

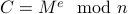

For Alice to read our encryped message  , she simply needs to

use her private key

, she simply needs to

use her private key  and compute:

and compute:

The fact that Alice can actually read the encrypted message is due to the following result:

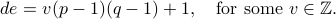

Let  be distinct prime numbers and

be distinct prime numbers and  .

Suppose that

.

Suppose that  satisfy the equation

satisfy the equation

Then for any  ,

,

This proposition follows from Fermat's little theorem and the Chinese remainder theorem.

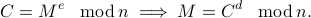

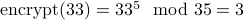

Example 5: encryption

Let us illustrate this:

Choose

and

and  . We have

. We have  and

and  .

.Let us choose

.

.We have to find

so that

so that

. We have

. We have  and

and  .

.Verify that

.

.The private key is

. The public key is

. The public key is  .

.

Using public key  and message

and message  ,

we have

,

we have  .

.

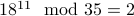

To decrypt, we have to compute

=

=  .

.

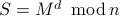

Example 6: authentication

The proposition above can be used not only for encrypting messages, but also for authentication.

Let's say Alice, equipped with a public key  and a

private key

and a

private key  , sends a message

, sends a message  to Bob.

to Bob.

For simplicity, let's assume that  can be represented by an integer between 1 and

can be represented by an integer between 1 and  . (Otherwise we can use the hash value of

. (Otherwise we can use the hash value of  .)

.)

To assure Bob that the message is from Alice, the following procedure can be taken:

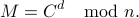

Alice “signs” the message using the encrypted signature

. (Note that the private key is used here.)

. (Note that the private key is used here.)Alice includes the encrypted signature

along with the

message

along with the

message  to Bob.

to Bob.When Bob gets the message

and the signature

and the signature  ,

using Alice's public key Bob computes

,

using Alice's public key Bob computes  ,

which should be the same as the message

,

which should be the same as the message  itself.

itself.

Fast modular exponentiation

In practice, we do not compute the exponentiation

before taking modulo! We would use a fast exponentiation

algorithm to compute

before taking modulo! We would use a fast exponentiation

algorithm to compute  for any give positive

integers

for any give positive

integers  .

.

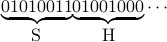

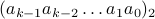

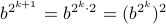

The key is to note that if if  has the binary representation

has the binary representation

,

then

,

then

so

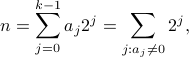

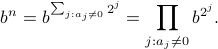

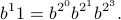

As a simple example: if  , then

, then  , so

, so

Noting that  ,

we don't even have to compute each of the factors

,

we don't even have to compute each of the factors

,

,  ,

,  individually. Combining all these

little observations together, we arrive at the fast modular

exponentiation algorithm:

individually. Combining all these

little observations together, we arrive at the fast modular

exponentiation algorithm:

int modexp( unsigned int b, unsigned int n, unsigned int m ){ int out = 1; int power = b % m; int i; /* insert routine computing the binary representation of n stored in some array a[0], ... a[k-1]*/ for ( i=0; i<k; i++ ){ if ( a[i]==1 ) { x = ( x*p ) % m; } p = ( p^2 ) % m; } return x; }

Breaking RSA

Let us assume that some one has access to the public key  . What stops them from finding out

. What stops them from finding out  , the secret key?

, the secret key?

After all,  . Therefore, by factorizing

. Therefore, by factorizing  , we can find

, we can find  and repeat the process for ourselves to compute

and repeat the process for ourselves to compute  and

and  . Once

. Once  is known then the whole scheme goes kaput.

is known then the whole scheme goes kaput.

Problem (Factoring) Given a number  that we are told is the product of two as yet unknown prime numbers

that we are told is the product of two as yet unknown prime numbers  , finding out

, finding out

is a hard problem.

is a hard problem.

In order to convince you that factoring a large number say  digits is hard, your first programming assignment that will be

out this monday asks you to try and write a factoring routine that given a number

digits is hard, your first programming assignment that will be

out this monday asks you to try and write a factoring routine that given a number  finds a prime factor

finds a prime factor  of

of  .

You can use any method to do so. However, if you are clever about this, we will have a class competition and your code

may win the competition. :-)

.

You can use any method to do so. However, if you are clever about this, we will have a class competition and your code

may win the competition. :-)

Combinatorially Hard Problems

There are problems in CS which do not have any known algorithms. The class of problems is called NP standing for Non-Deterministic Polynomial Time.

Claim Factoring a number  is an example of a hard problem.

is an example of a hard problem.

int factor(int n){ int i; for (i = 0; i < n;++i) if (Divides(i,n)) return i; return NO_FACTOR; }

Time taken to factor by best known algorithm is roughly  .

However, does that preclude a clever and faster algorithm?

.

However, does that preclude a clever and faster algorithm?

The best known factoring algorithm is the general number field sieve. Even though

it is worst case exponential, it has been used to factor large number of upto a  decimal

digits.

decimal

digits.